A few weeks ago I took my six year old daughter to a Scratch workshop at our local public library. I had heard about Scratch, but had not really seen it in action, and was very curious to see how my kid would take to it.

The workshop leader gave a very brief intro to the platform and did a simple sample program to get us started. He also had printed out the learning cards from the Scratch website, which give various samples and the specific code blocks to use to complete them.

By the end of the hour, we had implemented and adapted the program from one of the tutorials to make a picture of a cat chase a picture of a fish, and play a ‘meow’ sound whenever it ‘caught’ it. My daughter had a lot of fun, and now has added ‘can I play Scratch’ to her list of tech related requests, after 1. Can I watch a movie? and 2. Can I play on the iPad?

For those who may not be familiar with it, Scratch is a project from the MIT media lab. There is a great TED talk about its origins. The user interface is at the same time kid friendly and sophisticated.

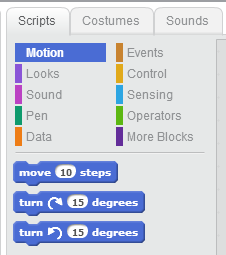

Programming in Scratch involves selecting a sprite and assembling a list of commands by dragging-and-dropping them on to a program canvas. The commands are color coded, and snap together Lego-style. You can have multiple sprites, and all the basic programming constructs are there, including conditions, loops, variables, events, and properties.

While Scratch is one of a growing number of platforms intended to introduce children to programming, it makes me wonder if it is the future of programming. Given that a whole generation of kids may grow up using Scratch, and consequently think that programming is a drag-and-drop, snap-together experience, I wonder if they will be disappointed to know that in real life, programming is a lot of typing.

I have a lot of respect and admiration of Andrew Hunt and David Thomas, authors of The Pragmatic Programmer. One of their tips is simply “Write Code That Writes Code”. They liken code-generators to templates and jigs used by woodworkers to use for repeated tasks. In some regard, Scratch is a code generator, in fact, quite a dynamic one. The click-together code blocks abstract out the core usage into a simple UI based entity, suitable for even a 6 year old to comprehend.

As a professional developer, I have always had a love-hate relationship with code generation tools. Part of me is a purist, wanting to write and own my own code, line by line. Part of me sees the HTML generated by Microsoft Word and wants to throw up. I have always held that writing code and gaining the experience and understanding of what is really going on is more valuable than just getting something generated quickly. But would I be happier to be able to quit typing line after line and instead drag-and-drop blocks on to the canvas? Would I feel in control enough of the output to appreciate the simplicity and convenience that the canvas offers?

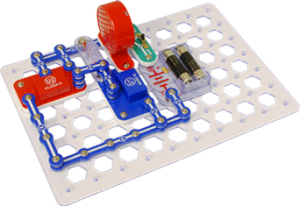

A more tangible analog to Scratch in the physical world are SnapCircuits. This ingenious kit allows kids to design and assemble electronic circuits and systems using snap-together components that conduct electricity through the contact points. There are switches, batteries, lights, bells, capacitors, and resistors. Using a underlying grid, you simply assemble the circuit by placing and connecting the individual parts. All the realities of electronics are there, just in a kid-friendly mode. Ohm’s law holds true for SnapCircuits just as it would any other electrical system.

But would you wire a house using SnapCircuits? Would we want to, given the chance? Wrapping wires around screws has worked for decades, right? Are these ‘snap-together’ systems only suitable for children?

If a system or new code-writing methodology would let me as a developer build systems faster, then there certainly is value to that. But are we too ‘mature’ to consider ‘kid-friendly’ methods as the way to achieve those gains? Perhaps my daughter’s generation will demand that shift, and they’ll have the bright minds at MIT who created Scratch to thank for it.

Leave a Reply